Firstly, a definition of Risk weighted assets from http://lexicon.ft.com/Term?term=risk_weighted-assets

Risk-weighted assets are computed by adjusting each asset class for risk in order to determine a bank's real world exposure to potential losses. Regulators then use the risk weighted total to calculate how much loss-absorbing capital a bank needs to sustain it through difficult markets.

Under the Basel III rules, banks must have top quality capital equivalent to at least 7 per cent of their risk-weighted assets or they could face restrictions on their ability to pay bonuses and dividends.

The risk weighting varies accord to each asset's inherent potential for default and what the likely losses would be in case of default — so a loan secured by property is less risky and given a lower multiplier than one that is unsecured.

Under the Basel II banking accord, which still governs most risk-weighting decisions, government bonds with ratings above AA- have a weight of 0 per cent, corporate loans rated above AA- are weighted 20 per cent, etc. The rules also attempt to classify assets by their credit risk, operational risk and market risk.

And now for the article

Doubts rise over gauge of lenders health

The Weekend Australian

David Enrich and Max Colchester, The Wall Street Journal

Saturday, 23rd June, 2012

LONDON: Regulators and investors are concerned that some European banks are artificially boosting a key measure of their financial health, a worry that is further eroding market confidence in Europe's banks.

Such concerns have been building for more than a year, but they have intensified recently, with a number of banks announcing they intend to increase their capital ratios (a key gauge of their abilities to absorb future losses) partly by tinkering with the way they assess the riskiness of their assets. Spanish banks are among those that have announced plans to boost their capital ratios by "optimizing" their risk weightings.

A number of European regulatory bodies have opened reviews into the matter. Britain's Financial Services Authority has been among the most aggressive, recently vetoing some banks' proposed ways of assessing their assets. At issue is the way banks calculate and disclose their capital ratios. The ratios are made up of certain types of equity expressed as a percentage of the bank's "risk-weighted assets", a fuzzy measure that an increasing number of regulators and investors fear is subject to abuse by banks.

The idea behind assessing capital as a proportion of risk-weighted assets is that not all assets are created equal. A bond issued by a blue-chip company is presumably less likely to incur losses than a mortgage to a heavily indebted homeowner. Under the risk-weighting systems, banks are permitted to hold less capital against safer assets than they have to hold against riskier ones. But banks enjoy wide discretion in how they assign weightings to different assets. If banks deem certain assets to be low-risk, that shrinks the denominator of the ratio and has the effect of boosting the banks' capital ratios.

A growing body of research by regulators, analysts and other experts indicates the practice is conducted inconsistently among banks and countries and is prone to manipulation. Pressure is mounting to use a standardized method of setting the risk weightings.

If banks underestimate the riskiness of their assets, their cushions to absorb losses could prove in a crisis to be perilously thin. Relying on risk weightings "is like asking your children to grade their own homework," Westhouse Securities strategist James Ferguson said. "It's crucial that nothing has gone wrong with these calculations, or we're in trouble."

Legal & General Investment Management fund manager Richard Black said the current approach undermined confidence in the system, and this forced investors to require that banks hold more capital.

The concerns are intensifying now because lenders have until the end of June to comply with a European Banking Authority directive to come up with more than €100 billion ($125bn) of new capital, a bid by regulators to alleviate concerns about the health of the continent's financial system. In a progress report earlier this year, the EBA announced banks had outlined plans to fill about 16 per cent of their holes by adopting new risk-weighting models or by tinkering with existing ones. The EBA and other regulatory bodies, such as the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, are identifying problems in how banks calculate risk weightings and trying to iron out inconsistencies between countries and institutions. Their goal is to preserve the credibility of international bank capital rules.

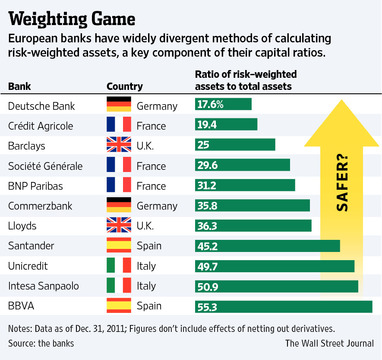

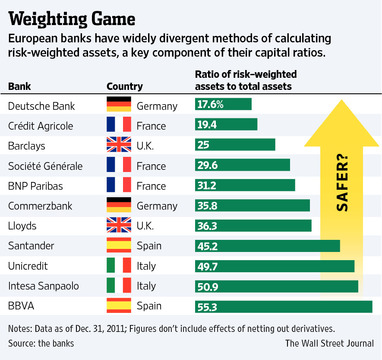

There are wide discrepancies in how banks assess the riskiness of their assets. Deutsche Bank was holding €2.16 trillion of assets last year, but on a risk-weighted basis this has shrunk to €381bn, a ratio of 18 per cent i.e. only €381bn are considered to be at risk. And Spain's Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria was holding about €331bn of risk-weighted assets out of €598bn of total assets, a ratio of 55 per cent.

The differences could simply reflect the varying levels of risk on banks' balance sheets. By those figures, Deutsche Bank's assets are overall much safer than BBVA's. But some investors and regulators are starting to treat low risk weightings as red flags. "Higher RWA density is now considered as an indication of more prudent risk measurement, where banks are less likely to 'optimize' the computation of their risk-based capital ratios," two International Monetary Fund researchers wrote in a paper.

With investor skepticism mounting, some banks have started boasting to investors about their high ratio of risk-weighted assets to total assets. In a presentation to investors earlier this year, BBVA touted its 55 per cent ratio as highest among its peer group.

In a presentation to investors this spring, Deutsche Bank finance chief Stefan Krause said the bank's low weightings reflect its safe balance sheet, which includes lots of loans to healthy German companies.

To see how banks can improve their capital cushions by reducing risk weightings, consider the case of Lloyds Banking Group. The big British bank in 2010 switched the models it was using to calculate risk weightings on residential mortgages. The new model spat out average risk weightings of 16 per cent, down from 21 per cent in the previous system.

Assume that Lloyds is required to maintain a 9 per cent ratio of capital to risk-weighted assets. If the £369 billion ($US580 billion) of mortgages received an average 21 per cent risk weighting, Lloyds would have to hold capital representing 9 per cent of £77 billion of assets, or £6.9 billion. With an average risk weighting of 16 per cent, the capital requirement falls to about £5.3 billion. A Lloyds spokeswoman said the change in average risk weightings was based on the integration of different mortgage portfolios and that Financial Services Authority regulators approved the switch.

** End of article