Fugitive's hunters came out of the night

The Australian

Tuesday, May 3, 2011

|

Below is an extract from an article on Afghanistan 1978-1992 and its role in the fall of the USSR

http://www.afghan-web.com/history/articles/ussr.html

Afghanistan became a unified country in 1747 under the leadership of an ethnic Pashtun leader, Ahmad Khan of the Sadozai (later named Durrani) clan of the Abdali tribe. It is under this tribe that the leadership of Afghanistan rested until the 1978 'revolution'.

The question over the motive of the Soviet Union in Afghanistan may be raised. Different authors have put forward a long list of issues which may have enticed the Russian invasion, but they all agree that both countries had a long and close relationship with one another, and the government of Afghanistan was one of the first to recognize the Bolshevik regime. Afghanistan had the largest per capita economic aid program with the Soviet Union before the Communist coup, the Afghan military was trained in the Soviet Union, and there was no military equipment supplied by the U.S. to the government during Mohammad Daoud's office as Prime Minister (1953-63) and President (1973-78).

The notion of self identity and nationalism which has had popular appeal in the Middle East since the nineteenth century, reached Afghanistan in the 1960's and created a popular dynamic resulting in the evolution of the leftist and rightist parties. In 1964 a liberal constitution initiated by King Zahir permitted multi-party elections in the Parliament and other government offices in Afghanistan. Moscow needed the service of an Afghan Communist party. Thus the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) was established in January 1965 by a group of intellectuals. Meanwhile, Conservative Islamist opposition was formed during the 1960's when the Pakistani Jama'at-i Islami, headed by 'Abdul 'Ala Maududi, tried to establish a sister organization in Kabul, with the help of some theology professors (graduates of Al-Azhar University, Egypt) at the Theology Department of the University of Kabul, aiming to revive the ideals of Muslim Brethren. During the Soviet occupation and the civil war that followed these leaders emerged as the major players on the Afghan scene.

The PDPA split into Khalq [People] and Parcham [Banner] factions, but were reunited under close Soviet patronage in 1977. President Daoud tried to eliminate the PDPA in Spring 1978 by arresting its leaders. This action triggered a classic Coup d'etat the next day. An armored brigade took over the presidential palace and killed everyone inside. Three days later the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan was declared, and Nur Mohammad Taraki announced as the president. Although it is argued that Moscow did not directly trigger the coup, one can point out that it did nothing to prevent it either. Thus, while the internal dynamics of the PDPA may have outpaced Soviet strategy, regardless, the damage had been done.

The neighboring countries were not however greatly alarmed by Moscow's / PDPA's take-over, because the regional balance of power still had not changed. Only Pakistan was worried about a stronger and tougher Kabul and thus supported the anti-government elements. The West, also, did not yet see the 1978 coup as an expansion of the Soviets towards the warm waters.

Following a power struggle between President Taraki and his Minister of Foreign Affairs, Hafizullah Amin, Amin's bodyguards assassinated President Taraki in September 1979 and Amin began a ruthless subjugation of the opposition, which then consisted of two-thirds of the country. Shaken by peasant revolts, urban upheavals and bloody internal feuds, the regime was on the verge of collapse when in December 27, 1979 the Soviets decided to intervene, killing Amin and replacing him with Babrak Karmal. After Karmal's failure to bring peace to the country, he was replaced by Minister of State Security, Dr. Najibullah in May 1986. Najibullah was to remain president until the Mujaheddin coalition took power in 1992.

In establishing the parameters, one could not put a price on the casualties, however it is necessary to apply some figures to it. In fighting the Soviets the Afghans suffered about two million dead (mostly civilian), economic devastation, over five million displaced citizens, and such political and social disintegration that the very future survival of Afghanistan as a state is still questionable. The war for the Soviets without much exaggeration meant nothing less then national suicide, even if one counts Afghanistan just as a catalyst for the breakup process of the Soviet Union.

Economically speaking, the cost of the war varies, according to the varying Soviet figures, but the most agreeable figure is given as $8.2 billion per year. As for casualties, it too is an arguable topic, due to the strict censorship of the Soviet Union. The official 15,000 dead is a gross underestimation. Experts agree that at least 40,000 - 50,000 Soviets lost their lives in action, besides the wounded, suicides, and murders. The ultimate political cost, however, was at least the breakup of the surface glaze which had hidden much of the internal decay for decades. This, in part, would not have been possible without the great contributions of communications technology which were placed at the disposal of the populace [mostly after the Afghan War, i.e. fax machines and the free and uncensored Media (due to Glastnost)], all of which were capable of reporting the slightest news around the world and all over the USSR.

However, it is the social costs that I want to emphasize. Some of my sources have focused on different frames of social breakdown as a result of the war. I will go over all of them briefly. Corruption is on the top of every list. One example given by Arnold is that the price-tag for a medical exemption from Chernobyl nuclear cleaning, in 1987, was 500 rubles, and 1000 rubles to avoid going for military service in Afghanistan. Drugs were another problem facing the society upon the return of the Russian Afghan veterans. Virtually all 546,200 troops who served in Afghanistan had the chance to experiment with drugs for the first time. Cheaper and easier to come by than alcohol in the Afghan bazaars, often drugs changed hands with guns and ammunition.

Yet a greater problem were the Afghan veterans, or Afgantsy, who returned to a country which deemed their sacrifice a mistake. Most of these soldiers suffered psychological problems, either by losing their minds or turning into a life of violence, including becoming involved with the local Mafia. Perhaps the sharpest criticism and opposition came from Andrei Sakharov, who on June 2, 1989, in the Congress of Deputies, shocked the nation and the deputies by calling the Soviet involvement in Afghanistan a criminal act and a war against an entire people. This is yet another example of a daring stand against the feared system; it is particularly interesting because the confrontation came from a distinguished political personality who was taking this stance.

On the civilian side, the people did not know of the 1979 invasion until three days after the invasion. And for the first year of the war the government denied any casualties in Afghanistan. In order to keep the war hidden the soldiers who were sent to Afghanistan were mainly chosen from the Baltic Sea area, Russia (Central Asia to a lesser extent), and were recruited from small villages. But even with assuming utmost precaution the government could not hide the invasion or its consequences.

Some sources focus on public opinion and the eventual escalation of protests during and then after the war, starting with underground papers and protest demonstrations at soldiers' funerals and grave sites (which were on small scale during the war, however). Although any protest was being immediately and severely put down (for the very act of opposition against the political establishment was regarded as high treason) no force could control the popular discontent of the Soviets, thus, protests were becoming more frequent and better attended. "I believed - I really believed," said a retired Soviet schoolteacher, of her lifelong party membership, in Fall of 1990. A Russian biologist related in early 1992 that "they said we were the happiest people in the world. How were we to know differently?" (Arnold, 200). Such actions are indicative of not only the mass frustration but also of political break-down.

According to Arnold, the Soviet Empire stood on three pillars: Military, KGB, and Communist party, and argues that the Afghan War ate into these pillars, weakening them to the point of break-down. For example, when key military and KGB commanders refused to follow Dmitris Yazov and Valdmiri Kryuchkoo's commands in August 1991 to storm the Russian Parliament where Boris Yeltsin was holding out, it was a decisive signal that the chain of command had lost its effective control. Also noteworthy is that among the civilians who manned the barricades around the parliament building and defied the tanks, there were a sizable contingent of the Afgantsy.

A channel through which a number of the Soviet people expressed their anger, frustration, and discontent was the independent free press. In magazines like Ogonyok people's letters were being published and the journalists gave accounts of the war based on personal experience. Two of my source, Small Fires and The Hidden War mainly focus on such publications. To show veteran's discontent with the government, I am including part of a letter, written by an Afgantsy Senior Lieutenant, to the Ogonyok magazine: ...I will send you a letter with all the details about how some there [Afghanistan] "did battle," received and then were deprived of battle decorations, falsified the lists of those who would receive decorations, redistributed equipment and personal gear, about what our superiors drank, what the higher-ups had for dinner and what the majority ate, where goods for the Afghan population disappeared to, how the officers made cripple of their soldiers and ignored murders and suicides, about the tragic events in battle that were committed with the full knowledge and under the orders of high officials, how we lived and how they, the "regimental elite," lived, about how lists of those decorated were not issued according to the rules because of the personal enmity of superiors to their subordinates, how housekeepers, bathhouse attendants, and gardeners were rewarded, and in general about anything and everything. (Borovik 286-7)

Economic devastation, political suppression, despotic rule, and forced virtues were Stalinistic old-school policies, which held the chains surrounding a society that no longer could be held from change. Afghanistan was a major factor in breaking the myths which had surrounded the Soviet Empire for decades. Acknowledging the speedy implementation of Perestroika and Glasnost, coupled with a breakdown of the economics and changing Soviet ideology were elements breaking apart the Soviet Union.

Rameen Moshref

from http://www.oxuscom.com/greatgame.htm

711 An Arab army conquers Sind (in northern India)

997-1026 Mahmud of Ghazni (in Afghanistan) raids northern India

1175-1206 Mohammad of Gor (in Afghanistan) invades India six times

1219-1240 Russian principalities fall to the Mongols

1398 Timur (also known as Tamerlane) of Uzbekistan sacks Delhi

1480 First armed confrontation between the Russians, under Ivan III (the Great, 1462-1505), and the Mongols on the River Ugra ends in both sides fleeing from each other

1526 Babur of Uzbekistan invades India and establishes the Mogul Empire

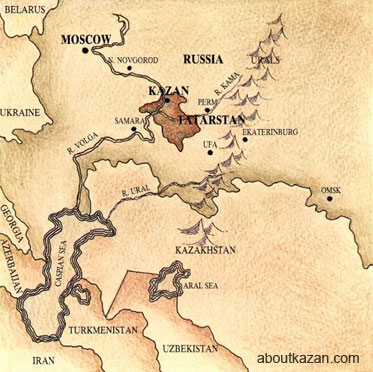

1553 Tsar Ivan IV (the Terrible, 1547-1584) captures the

Mongol

fortress of Kazan

1553 Tsar Ivan IV (the Terrible, 1547-1584) captures the

Mongol

fortress of Kazan

1717 Russian expedition to Khiva (Uzbekistan) sent by Tsar Peter the Great (1682-1725) under leadership of Prince Alexander Bekovitch ends in the slaughter of the Russians in Khiva

1725 Death of Peter the Great and beginning of story that he had commissioned his heirs to possess India and Constantinople as the keys to world domination

1737 The Russians build the Fortress of Orenburg north of the Caspian Sea in order to subdue and control the Kazak tribes

1739 Nadir Shah of Persia invades India and briefly seizes Delhi

1756 Ahmad Shah Durrani of Afghanistan invades India and sacks Delhi

1791 Tsarina Catherine the Great (1762-1796) considers a plan to "deliver" India from the growing British influence there

1798 Napoleon's invasion fleet departs from France, bound

for

Egypt and India (May)

Lord Wellesley, Governor-General of India, starts to add territory

to

Britain's growing empire in India

Admiral Nelson defeats the French fleet near Alexandria, thus eliminating the threat to India (Aug.)

1800 Capt. John Malcolm heads up a British diplomatic mission to the Persian Shah in Teheran which results in two treaties being signed (summer)

1801 Tsar Paul I (1796-1801) proposes to Napoleon a joint

Franco-Russian

invasion of India

Paul dispatches an invasion force to India, shortly thereafter

recalled

upon his death (Jan.)

Tsar Alexander I (1801-1825) annexes Georgia (Sept.)

1804 Russian armies lay siege to Yerevan, Armenia, a Persian possession, but Britain does not come to Persia's aid (June)

1807 Napoleon signs a treaty with the Persian Shah which

severs

Persia's relations with Britain and allows French troops right of

passage

through Persia (May)

London learns that Napoleon, after defeating the Russians, has proposed to Alexander I a joint Franco-Russian invasion of India (summer)

1808 Malcolm's second mission to Persia, resulting in a new treaty with Britain that prohibits the troops of other countries crossing Persian territory to attack India (May)

1810 Lt. Henry Pottinger and Capt. Charles Christie travel from Baluchistan (in northern India) to Persia, spying out a possible approach route to India for an invading army (March-June)

1812 Napoleon invades Russia, thus removing any possibility

of

a joint invasion of India (June)

A Russian force under General Kotliarevsky annihilates the Persian army on the River Aras and then captures the Persian stronghold of Lenkoran on the Caspian Sea

1813 The Treaty of Gulistan forces the Persian Shah to

surrender

all his territory north of the River Aras, including Georgia, Baku and

naval rights on the Caspian Sea

John MacDonald Kinneir publishes A Geographical Memoir of the Persian Empire, which outlines possible attack routes to India

1814 Alexander I enters Paris in triumph (Mar.)

The Congress of Vienna redraws the map of Europe, with Russia receiving a significant portion of Poland

1817 Sir Robert Wilson writes A Sketch of the Military and Political Power of Russia, warning of Russia's territorial expansion

1819 Capt. Nikolai Muraviev undertakes a solo mission to Khiva (Uzbekistan) to make contact with the Khan, evaluate his military power and find out the plight of the Russian slaves there(summer-Dec.)

1820 William Moorcroft embarks on a journey from India via

Ladakh

to Bukhara (Uzbekistan) to find horses for the East India Company (Mar.)

Russian mission to Bukhara establishes trade links with the Khanate and opens doors for the import of Russian goods (Oct.)

1825 Moorcroft reaches Bukhara (Feb.)

Moorcroft and his companions die near Balkh, Afghanistan (Aug.)

Russian troops, under General Yermolov, occupy the area between Yerevan and Lake Sevan, resulting in the Persians raiding into Russian territory and recapturing Lenkoran, followed by the Russians recapturing Yerevan and ultimately defeating the Persians (Nov.)

1828 Treaty of Turkmanchi adds Yerevan and Nakitchevan to

the

Russian Empire and reduces Persia to a virtual protectorate of Russia

Col. George de Lacy Evans publishes On the Designs of Russia, warning of Russia's plans to attack India

1829 Alexander Griboyedov, the Russian ambassador to Persia,

is murdered in Teheran by a mob (Jan.)

Peace Treaty between Russia and Turkey negotiated at Adrianople

gives

Russia free passage through the Dardanelles and trading privileges in

the

Ottoman Empire (Sept.)

Evans publishes On the Practicability of an Invasion of British

India

Capt. Arthur Conolly departs from Moscow for India via the Caucasus (autumn)

1830 Conolly arrives in Herat in Afghanistan (Sept.)

1831 Conolly arrives on the northwest frontier of India

(Jan.)

A British mission under Lt. Alexander Burnes departs up the Indus River to deliver horses to Ranjit Singh, the Sikh ruler of Lahore, as well as to discover the feasibility of transporting British goods up the Indus (Jan.)

1832 Burnes embarks on a journey through Afghanistan to Bukhara, meeting Dost Mohammad, the Afghan ruler, and the Vizier of Bukhara (Mar.)

1833 Burnes and his party return to Bombay (Jan.)

A large fleet of Russian warships drops anchor off Constantinople to

protect the Ottoman Sultan from an attacking Egyptian army (Feb.)

In exchange for saving it from the attacking Egyptians, Turkey signs a treaty with Russia giving the latter exclusive access to the Dardanelles (summer)

1834 Burnes publishes Travels into Bokhara, an

account

of his travels

Conolly publishes Journey to the North of India, an account

of

his travels

David Urquhart makes first contact with the Circassians (an area of Russia just north of Georgia) and becomes committed to their cause of independence from Russia

1835 Dost Mohammad secretly approaches the Russians regarding getting help to recapture Peshawar from Ranjit Singh, an ally of Britain (Oct.)

1836 Urquhart becomes First Secretary at the British Embassy

in Constantinople

Sir John McNeill publishes The Progress and Present Position of

Russia

in the East, detailing Russian expansion over the previous century

and a half

The Vixen, a British vessel, sails across the Black Sea to "trade" with the Circassians, resulting in the vessel being seized by the Russians (Nov.)

1837 Lt. Henry Rawlinson encounters Capt. Yan Vitkevitch and

a party of Cossacks in eastern Persia, carrying gifts intended for Dost

Mohammad in Kabul (autumn)

Lt. Eldred Pottinger enters Herat on a reconnaissance mission (Aug.)

Burnes, dispatched by Lord Auckland, the Governor-General of India,

arrives in Kabul (Sept.)

The Persians begin their siege of Herat (Nov.)

1838 Auckland sends a letter to Dost Mohammad, telling him

to

abandon the idea of recovering Peshawar (Jan.)

Dost Mohammad receives Vitkevitch in Kabul, resulting in Burnes

leaving

to return to India (Apr.)

Russian-led Persian attack on Herat, repelled under the direction of

Pottinger (June)

British troops land on Kharg Island in the Persian Gulf, causing the

Persian Shah to break of his attack on Herat (June)

Britain, Ranjit Singh and exiled Afghan ruler Shah Shujah sign a

secret

agreement enabling the British to invade Afghanistan and overthrow Dost

Mohammad (June)

Col. Charles Stoddart arrives in Bukhara (Dec.)

1839 Robert Bremmer publishes Excursions in the Interior

of

Russia and the Marquis de Custine publishes La Russe en 1839,

both of which warn of Russia's designs in Asia

The British invade Afghanistan via the Sind, launching the First

Afghan

War (spring)

The British and Shah Shujah enter Kandahar (Apr.)

The British capture Ghazni (May)

The British enter Kabul without a fight, Dost Mohammad having fled

(July)

Stoddart is arrested in Bukhara and thrown in the Emir's bug pit

(Aug.)

A Russian expedition, led by General Perovsky, departs from Orenburg

for Khiva (autumn)

Capt. James Abbott departs from Herat for Khiva (Dec.)

1840 Abbott arrives in Khiva (Jan.)

A Russian expedition to Khiva turns around before reaching its goal

and returns to Orenburg, due to extreme weather (Feb.)

Abbott sets out from Khiva for Ft. Alexandrovsk on the eastern shore of the Caspian Sea (Mar.)

Lt. Richmond Shakespear departs from Herat for Khiva (May)

Shakespear arrives in Khiva (June)

Shakespear sets out from Khiva for Ft. Alexandrovsk with freed

Russian

slaves (Aug.)

Conolly sets out from Kabul for Bukhara (Sept.)

Shakespear arrives in St. Petersburg en route to London (Nov.)

Dost Mohammad surrenders to the British and goes into exile in India (Nov.)

1841 Conolly arrives in Bukhara (Nov.)

Burnes and others are murdered by a mob in Kabul (Nov.)

Sir William Mcnaghten, political head of the British mission to Kabul, and others are murdered by Mohammad Akbar Khan, son of Dost Mohammad (Dec.)

1842 The British, under General William Elphinstone, leave

Kabul

after Akbar agrees to guarantee their safety, but are massacred by

Afghan

tribesmen en route to the British garrison at Jalalabad (Jan.)

The British send reinforcements from India to Jalalabad and Kandahar

to prepare to march on Kabul (Mar.)

Execution of Conolly and Stoddart by Emir Nasrullah of Bukhara

(June)

British reinforcements, under Generals Pollock and Nott, reach Kabul

and Shakespear rescues the British hostages Akbar has been holding

(Sept.)

After razing the covered bazaar, the British leave Kabul for good (Oct.)

1843 Dost Mohammad returns to the throne in Kabul (Jan.)

The British seize Sind

1844 Tsar Nicholas I (1825-1855) pays a state visit to Britain and states that he has no more territorial ambitions in Asia (summer)

1845 Rev. Joseph Wolff publishes Narrative of a Mission to Bukhara after journeying to Central Asia to determine the fate of Conolly and Stoddart

1848 Revolutions break out across Europe, including Paris, Berlin, Vienna, Rome, Prague and Budapest, prompting Nicholas I to clamp down on freedoms in Russia and to dispatch an army to Hungary to crush the uprising there

1849 The British seize the Punjab, detaching Kashmir as a separate state with a ruler friendly to them

1853 The Russians advance as far as Ak-Mechet on the Syr Darya River in Kazakhstan

1854 During the Crimean War, the British and French lay siege to Sebastopol on the Black Sea (Sept.)

1855 Nicholas I dies (possibly having committed suicide) (Mar.)

1856 The Second Opium War between Britain and China

Prince Alexander Gorchakov becomes Russian Foreign Minister

Tsar Alexander II (1855-1881) negotiates a peace treaty with Britain

and France and the Congress of Vienna imposes restrictions on Russia,

including

a ban on naval activity in the Black Sea (Feb.)

Herat falls to the Persians (Oct.)

A British military force captures Bushire on the Persian Gulf,

causing

the Shah to withdraw from Herat and abandon his claims to it (Dec.)

Britain adopts the policy of "masterly inactivity" in its relations with Russia

1857 The Indian Mutiny threatens British rule in India (May)

1858 Nikolai Khanikov, a Russian agent, attempts to make

contact

with Dost Mohammad but is rebuffed by him (spring)

The Indian Mutiny is finally suppressed (spring)

The India Act abolishes the right of the East India

Company

to rule in India and transfers all authority to the British crown

(Aug.)

Count Nikolai Ignatiev heads up a Russian mission to Khiva and Bukhara to discover how far the British have penetrated in Central Asia (summer)

1859 Ignatiev heads up a mission to Peking to get the

emperor

to formally cede to Russia territories they have captured following the

Second Opium War (spring)

The Russians finally defeat Imam Shamyl, bringing to an end resistance in the Caucasus

1860 After the British and French leave Peking, Ignatiev negotiates the Treaty of Peking with the Chinese, giving Russia a large territory north of the Amur River and the right to open embassies in Sinkiang and Mongolia (Nov.)

1861 40 million Russian serfs are emancipated as part of a program of liberal reform in Russia

1863 Dost Mohammad captures Herat

1864 The Russians advance on Central Asia, consolidating

their

southern frontier by capturing Chimkent, Turkestan, and other towns and

forts in the northern domains of the Khan of Kokand in Uzbekistan

Arminius Vambery travels through Central Asia

Gorchakov distributes a memorandum to the European powers to explain Russian advances into Central Asia (Dec.)

1865 Yaqub Beg arrives in Kashgar in Sinkiang from Kokand and goes about

consolidating his power in Kashgaria (Jan.)

1865 Yaqub Beg arrives in Kashgar in Sinkiang from Kokand and goes about

consolidating his power in Kashgaria (Jan.)

The Russians, under General Cherniaev, capture Tashkent, capital of Uzbekistan (June)

1868 The Russians, under General Kaufman, capture Samarkand in Uzbekistan

and

force the Khan of Bukhara to agree to becoming a Russian protectorate

(May)

Robert Shaw and George Hayward travel, separately, from Ladakh to Kashgar to establish contact with Yaqub Beg for trade and geographical survey purposes, respectively (Sept.-Dec.)

1869 The Russians build a permanent fortress at Krasnovodsk in Turkmenistan (where the dry bed of a former mouth of the Amu-Darya River once emptied into the Caspian Sea.) (winter)

1870 Hayward embarks on a journey to the Pamirs (the Hindukush Mountains) and is murdered by tribesmen near Darkot, between Chitral and Gilgit (July)

1871 The Russians, under General Kaufman, invade the Ili

Valley in Sinkiang,

annexing it (June)

The British establish a direct submarine cable link between London and India

1872 The Russians dispatch a mission to Yaqub Beg's court to discuss trade terms designed to favour Russian goods over British ones (spring)

1873 Russia acknowledges that Badakhshan and Wakhan are part

of the domains of the Afghan Emir and that Afghanistan lies within the

British sphere of influence (Jan.)

The Russians, under General Kaufman, capture Khiva (May)

British trade mission to Kashgar, headed up by Sir Douglas Forsyth

(summer)

Sher Ali, the Afghan Emir, approaches the British with a proposal for a defence treaty against the Russians, but is refused by the British

1874 Lt.-Col. Thomas Gordon and a small British party

explore

the Pamirs (spring)

Britain's Liberal government is replaced by the Tories under Disraeli, who abandon "masterly inactivity" and renew forward policies (spring)

1875 The Russians, under General Kaufman, capture Kokand in Uzbekistan,

after

an uprising against the Russians and the puppet Khan they had installed

there (Aug.)

The Khan of Khelat permanently leases the Bolan Pass and Quetta to

the

British (autumn)

Capt. Frederick Burnaby departs from Britain on his journey across

Russia

Central Asia (Nov.)

Rawlinson publishes England and Russia in the East

Uprisings in the Balkans against Turkish rule (summer)

1876 Burnaby reaches Khiva and meets with the Khan, now a

vassal

of the Russians (Jan.)

Burnaby returns to Britain, to write a book about his travels, A Ride to Khiva (Mar.)

1877 The Russians declare war against the Turks and begin

their

advance on Constantinople through the Balkans and from eastern Turkey,

but later halt their invasion short of Constantinople (spring)

Death of Yaqub Beg in Kashgar (May)

The Chinese recapture Kashgar (Dec.)

1878 The Congress of Berlin results in Russian gains in the

war

against Turkey being lost (July)

A Russian mission to Kabul results in the signing of a treaty of

friendship

between Russia and Afghanistan (Aug.)

The British inform Sher Ali that they intend to send a mission to

Kabul

and ask for safe passage (Aug.)

After Sher Ali rebuffs the British request for safe passage, the

British

march on Kabul, beginning the Second Afghan War (Nov.)

The Russians send military explorers to Herat, the Pamirs and Tibet, in anticipation of a planned invasion of India that is later called off (autumn)

1879 The British and the Afghans sign the Treaty of

Gandamak,

ending the war and granting significant concessions to Britain,

including

control of Afghan foreign policy (May)

The British mission, under Maj. Louis Cavagnari, reaches Kabul

(July)

The Russians attempt to capture the Turkmen stronghold of Geok Tepe,

but are defeated (Sept.)

The British mission in Kabul is attacked by an Afghan mob and all

are

killed (Sept.)

A British punitive force, under General Frederick Roberts, reaches

Kabul

(Oct.)

The British defeat an Afghan attack on them in Kabul (Dec.)

1880 Abdur Rahman, nephew of Sher Ali, returns from exile in

Samarkand to claim the Afghan throne (Feb.)

The Chinese threaten to take back Kuldja, in the Ili Valley, by

force

(spring)

The British garrison at Kandahar is defeated in battle at Maiwand,

near

Kandahar, by Ayub Khan, the ruler of Herat and Abdur Rahman's rival for

the throne (June)

The British agree to leave Kabul and let Abdur Rahman have the

throne,

in exchange for his promise to have relations with no other power but

Britain

(July)

Roberts' forces from Kabul defeat Ayub Khan, who is later defeated

and

driven out of Afghanistan by Abdur Rahman, who captures Herat (autumn)

The Russians begin to extend the Transcaspian Railway east from the

Caspian port of Krasnovodsk

The Tories are defeated by Gladstone's Liberals, leading to an abandonment of "forward policies"

1881 The Russians, under General Skobelev, capture Geok

Tepe,

slaughtering those who flee from the fallen fortress (Jan.)

The Treaty of St. Petersburg results in Russia returning Kuldja to China

1882 Arrival of Lt. Alikhanov in Merv to spy out Turkmen

defenses

of the city and prepare for annexation by Russia (Feb.)

Arrival of Nikolai Petrovsky, Russian Consul, in Kashgar

1884 Merv falls to the Russians (Feb.)

1885 Charles Marvin publishes several books on Anglo-Russian

relations, including The Russians at the Gates of Herat

Vambery speaks out in London on the Russian threat in Asia (spring)

The Russians, under Lt. Alikhanov, capture the Afghan town of

Pandjeh,

halfway between Merv and Herat (Mar.)

A British military survey party, under William Lockhart, is

dispatched

to map Chitral and Hunza (summer)

The Joint Afghan Boundary Commission begins its work of demarcating the Afghan boundary

1886 The Tories return to power in Britain and, as a result, return to a forward policy

1887 The Joint Afghan Boundary Commission settles the Afghan

border, except for the eastern frontier

Lt. Francis Younghusband travels across China from Peking to India (Apr.-Dec.)

1888 George Curzon travels through Central Asia and later

writes

Russia

in Central Asia and the Anglo-Russian Question (summer)

Scottish trader Andrew Dalgleish murdered in the Karakoram Pass area

1889 Younghusband leads an expedition to Hunza to warn the ruler against raiding British traders (Aug.-Dec.)

1890 Younghusband and George Macartney survey the Pamirs and travel to Kashgar, where Macartney becomes the British Consul

1891 Reports reach London that the Russians are planning to

annex

the Pamirs (July)

Younghusband encounters Russian troops in the Pamirs who have

claimed

Afghan and Chinese territory for the Tsar (Aug.)

The British and Kashmiris march against Hunza, resulting in its capture and incorporation into British India (Nov.)

1892 The Tories are defeated by Gladstone's Liberals in the British election

1893 The Russians clash with the Afghans and Chinese in the

Pamirs

Peter Badmayev, a Buryat Mongol, submits to Tsar Alexander III (1881-1894) a plan for bringing the Chinese Empire under Russian influence

1895 The British, under Major George Robertson, march on

Chitral,

placing their own choice of ruler on the throne (Feb.)

Umra Khan, ruler of Swat, lays siege to the British troops in the

palace

in Chitral (Mar.)

A British relief force, under Col. James Kelly, delivers the British in Chitral, ending the siege (Apr.)

1898 Russia gains the warm water naval base of Port Arthur

from

the Chinese

Lord Curzon becomes Viceroy of India

1900 The Boxer Uprising in China leads to the occupation of Peking by the European powers

1903 A British mission to Lhasa, Tibet, led by Younghusband,

is turned back by the Tibetans (Apr.)

The second British mission to Lhasa (Dec.)

1904 The Japanese attack the Russian fleet at Port Arthur,

initiating

the Russo-Japanese War (Feb.)

Tibetan troops are massacred by the British en route to Lhasa (Jan.)

The British mission enters Lhasa (Aug.)

1905 Port Arthur falls to the Japanese (Jan.)

The Japanese destroy the Russian Baltic Fleet in the Tsushima

Straits

(May)

Russia and Japan sign a peace treaty, ending the war (Sept.)

The British mission leaves Lhasa (Sept.)

The Liberals defeat the Tories (Dec.)

Revolution in Russia causes Tsar Nicholas II (1894-1917) to introduce Russia's first parliament, the Duma, which he later dissolves

1907 The Anglo-Russian Convention officially brings the Great Game to an end (Aug.)

1911 Fall of the Manchu dynasty in China and establishment of the Republic of China

1914 Britain and Russia enter World War I as allies (Aug.)

1917 The Russian Revolution leads to a collapse of the

Eastern

Front in the war and the Tashkent Soviet seizing power in Tashkent

(Oct./Nov.)

Creation of the Muslim Provisional Government of Autonomous

Turkestan

in Kokand (Nov.)

Lenin issues a call to Asia's millions to follow the example of the Bolsheviks (Dec.)

1918 Muslim Provisional Government of Autonomous Turkestan

informs

the Tashkent Soviet that it intends to elect a parliament in which 1/3

of the seats would be apportioned to non-Muslims (Jan.)

The Tashkent Soviet attacks Kokand, massacring thousands of Muslims

(Feb.)

First attempt by the Bolsheviks to capture Bukhara (Mar.)

Macartney is replaced by Col. Percy Etherton as British Consul in

Kashgar

(June)

The Bolsheviks kill Tsar Nicholas II and his family (July)

Col. Bailey crosses from Kashgar into Soviet Central Asia (July)

British forces clash with Bolsheviks near Ashkabad (Aug.)

Bailey arrives in Tashkent, followed soon after by Macartney (Aug.)

Bailey goes into hiding and White Russian leader Paul Nazaroff is

arrested

in Tashkent (Oct.)

World War I is brought to an end by the Armistice (Nov.)

1919 Anti-Bolshevik uprising in Tashkent led by Osipov

results

in Nazaroff's release but is quickly defeated by the Bolsheviks (Jan.)

British troops are ordered to withdraw from the Ashkabad region back

to Meshed, Persia (Feb.)

First meeting of the Communist International (Comintern) in Moscow,

with the purpose of establishing a world Soviet (Mar.)

King Amanullah of Afghanistan launches a brief and unsuccessful

invasion

of India, now known as the Third Afghan War (May)

Bailey leaves Tashkent as a Cheka officer, commissioned to find

himself

(Oct.)

Bailey leaves Bukhara for the Persian border (Dec.)

1920 Bailey and his party cross the border into Persia

(Jan.)

Special intelligence unit set up in India to counteract Bolshevism

and

monitor activities of the Comintern (Jan.)

Mikhail Frunze arrives in Central Asia to lead the Red Army against

the Muslim basmachi rebels (Feb.)

M. N. Roy, an Indian Communist, travels to Moscow to meet Lenin

(Apr.)

Nazaroff succeeds in escaping to Kashgar (summer)

The final defeat of the White Russian armies and the end of the

Allied

Intervention in the Russian Civil War (summer)

The Comintern, meeting in Baku, issues a call for Muslims to declare

a holy war against imperialism (Sept.)

The Red Army attempts to capture Warsaw, Poland, but is defeated

(autumn)

Roy proposes to train an army in Central Asia to invade India

(autumn)

Roy reaches Tashkent and sets up his secret military school to train

"The Army of God" for invading India (Nov.)

Baron Ungern-Sternberg leads his Cossack forces into Mongolia (autumn)

1921 Ungern-Sternberg attacks and captures Urga (Ulan

Bator),

Mongolia (Jan./Feb.)

Anglo-Soviet Trade Agreement, concluded between London and Moscow,

grants

partial recognition of the Soviet state and demands the end of Soviet

plans

to overthrow British rule in India (Mar.)

Ungern-Sternberg moves into Soviet territory, intent on wiping out

the

Bolsheviks, resulting in his defeat and capture by the Bolsheviks and

the

establishment of the Mongolian People's Revolutionary Government,

Moscow's

first client-state (May)

Ungern-Sternberg is executed in Novosibirsk, Siberia (Sept.)

Turkish General Enver Pasha meets with Lenin in Moscow, ostensibly

to

capture Chinese Turkestan and launch an invasion into India for the

Bolsheviks

(autumn)

Pasha arrives in Bukhara, where he switches allegiance to the basmachis (Nov.)

1922 Pasha is killed in battle against the Bolsheviks (Aug.)

Mikhail Borodin arrives in Britain and is later arrested and

deported

back to Russia (summer)

Etherton leaves Kashgar

1923 Lord Curzon, British Foreign Secretary, sends an

ultimatum

to Moscow, demanding that it withdraw its agents operating against

British

interests in Asia (May)

Borodin arrives in Peking and moves to Canton to help the Kuomintang government of Sun Yat-sen (autumn)

1924 Britain elects its first ever Labour government

(winter)

Britain accords full diplomatic recognition to the Soviet Union (Feb.)

1925 Death of Sun Yat-sen, resulting in Chiang Kai-shek taking control of the Kuomintang and a swing to the right in party policy (Mar.)

1927 Chiang Kai-shek turns on the Communists and leftists,

massacring

many (spring)

Raid on the Soviet Trade Delegation in London results in the British

government voting to sever ties with the Soviet Union (May)

The Canton Uprising results in the brief seizure of power by the Communists, followed by capture of the city by the Kuomintang (Dec.)

1928 Governor Yang Tseng-hsin of Sinkiang is assassinated and power is seized by Chin Shu-jen (July)

1929 Arrest of Indian Communists and the Meerut Conspiracy Trial (Mar.)

1930 Chin orders that the city-state of Hami should be absorbed into Sinkiang results in Muslim revolts against Chinese authority

1931 Muslim warlord Ma Chung-yin begins his march into Sinkiang (summer)

1933 A Soviet-backed coup topples Chin, who is replaced by Sheng Shi-tsai (Apr.)

1934 Ma's troops reach Urumchi and Stalin offers Sheng the use of Red Army troops to put down the rebellion (Jan.)

1934-38 Stalin's purges in the Soviet Union

1939 Non-aggression Pact signed between Germany and the Soviet Union (Aug.)

1939 Britain and India declare war on Germany (Sept.)

1941 Germany invades the Soviet Union (June)

1942 Sheng demands that Moscow remove its advisors from

Sinkiang

(Oct.)

Nazaroff dies in South Africa

1944 Sheng unleashes an anti-Communist witch-hunt, followed

by

an anti-Kuomintang witch-hunt

Sheng leaves Sinkiang to take up a post in the Republican government in Formosa (Sept.)

1949 Communist victory in China

1951 Borodin dies in a Stalinist labour camp

1954 Roy dies in India

1967 Bailey dies in England

|

IT'S time for the communists to party. It was 90 years ago today that the world's most powerful organisation was born, and it now eclipses even the Vatican in its unbridled authority. It has become the essential partner for Australia's economic prosperity, with the government announcing yesterday that trade with China last year reached an astonishing $105 billion.

Yet the party that oversees almost every aspect of China's life, especially its economy, remains little understood in Australia. Core questions such as its funding and how its leaders are chosen remain clouded even to Sinologists. Who would have guessed that after the other one-party regimes that emerged so potently during the 20th century had imploded or faded away, the Chinese Communist Party would have seized the centre of global influence as it has?

The party has given authoritarianism a new currency, especially among Western businesspeople, who form its most avid admirers. It has achieved this while maintaining intact virtually the entire suite of institutions Mao Zedong introduced when he established the People's Republic of China in 1949. But for all its success, the party, whose 80 million members comprise the wealthiest and most powerful people in the population of 1.3 billion, retains a brittle edginess born of its lack of legitimacy.

The party's right to rule still fundamentally emanates from its civil war victory three generations ago over a nationalist government worn down by its decade-long fight against the invading Japanese. "All power comes from the barrel of a gun," Mao pronounced.

In lieu of formalising that legitimacy by seeking electoral approval, since Mao's death in 1976 the party has relied chiefly on its impressive material catch-up with the rest of East Asia. That legitimacy also comes from the story of modern China, which the party has framed its own way. And it is sealed by the party's incorporation of the key emblems of what it means to be Chinese today: the flag, the state symbol, the national heroes and role models, the public rhetoric and, crucially, the People's Liberation Army — the party's army, accountable primarily to the party leadership.

The preamble to China's constitution entrenches the party's dominant role in the state: "Under the leadership of the Communist Party of China and the guidance of Marxism-Leninism, Mao Zedong Thought, Deng Xiaoping Theory and the important thought of Three Represents, the Chinese people of all nationalities will continue to adhere to the people's democratic dictatorship and the socialist road."

The Three Represents: "The party represents 1. the developmental needs of China's advanced production capacity, 2. the progressive direction of China's advanced culture, and 3. the fundamental interests of the broad majority" — General Secretary Jiang Zemin, 2000

It is the men of the standing committee of the political bureau of the party — no woman has yet attained such rank — who rule China, outranking the state council or cabinet, which is the highest arm of executive government. The last serious attempt to separate party from government was made by Zhao Ziyang when he was general secretary in the late 1980s. But the response to the 1989 nationwide protests, culminating in the killings in Tiananmen Square, included placing Zhao under house arrest until he died 16 years later, and his reforms faded with him, while the PLA's clout grew.

Since 1989, no significant political reform has been introduced despite experimentation in village elections and in "intra-party democracy", allowing members to choose between preselected candidates for local party positions. China remains the only country of its size not to be governed by a federation. It has a single time zone.

Economic reform has slowed to a crawl since the dynamic era of premier Zhu Rongji, who a decade ago took China into the World Trade Organisation and corporatised state-owned enterprises. China's manufacturing, opened to foreign and private owners, has conquered the world. But in an important new book, Red Capitalism, investment bankers Carl Walter and Fraser Howie, who have worked in China for decades, say China's finance system remains "an empire set apart from the world designed so that no one is able to take a position opposite to that of the government".

The CCP has become the party of stability, power and tradition, tentatively now even embracing Confucius, denigrated by the party's founders as an arch-reactionary. But when early this year a statue of Confucius was erected at the edge of Tiananmen Square, in the gaze of the great Mao portrait on the Gate of Heavenly Peace, the latter's continuing influence won the day and the statue was soon relocated inside a museum. "Dump Confucius into the sea!" Mao had urged.

The party has become a dynasty — albeit today one with a smoother transition model than the emperors — and its top leaders are cut off from contact with ordinary life in China almost as severely as the imperial families of old. Its leaders work, and some live, in Zhongnanhai, a walled city adjacent to the Forbidden City at the heart of Beijing.

The party was born in a burst of radical energy as new waves of revolutionary ideas pulsed across the world. On July 1, 1921, 13 young men seized by socialist and revolutionary ideas met in a ground-floor room of a modest, grey brick house in the French concession of Shanghai — then, as again today, a centre of international business — for the CCP's inaugural congress. They were representing a mere 60 members nationwide.

Among them was the former librarian Mao. The life-size wax model tableau presented at the site today features Mao at centre, bathed in a divine spotlight and addressing his apparent disciples. But they actually elected as the party's first general secretary, and then chairman, the absent Chen Duxiu, dean of Beijing University and editor of the influential publication New Youth. If they were to return today, the 13 would be perplexed to find their humble meeting place enfolded within Xintiandi — New Heaven and Earth — a cafe and shopping zone for affluent tourists and Shanghainese built by Hong Kong developer Vincent Lo.

The 250-year-old Qing dynasty had fallen a decade earlier, with Sun Yat-sen, universally viewed as the founder of modern China, becoming the first president of the new republic. The most powerful catalyst, though, was the Russian Revolution of 1917. Hendrick Sneevliet, a 38-year-old Dutchman, joined the 13 as Russia's Communist International (Comintern) representative, using the code name Maring. The party attempted for its first six years, with Lenin's encouragement, to build credibility from within the nationalists. But as Chiang Kai-shek took over from Sun, that scenario foundered. Mao then focused on establishing soviets (communal groups) in his rural Hunan homeland.

Already, China's communists, campaigning primarily among peasants, were taking a different road from their Russian comrades, whose revolution sprang from urban workers. Fifty years later the Chinese again set out in a distinctive direction, engaging economically with global business, from which the old Soviet Union remained aloof until its 1990 demise. When the nationalists started to encircle the communists, Mao decried the Comintern advice to wage a traditional war, seized the leadership, moulded the PLA as a guerilla force and led his rapidly dwindling force in the Long March (1934-1935) that ended at Yan'an in China's heartland province of Shaanxi.

There he purged all dissent, as the nationalists lost ground to the invading Japanese. Full-blown civil war followed the Japanese defeat in 1945, and the corrupt and exhausted nationalists finally fled to Taiwan, where in recent years a new model of liberal democratic Chinese governance has emerged.

The republican era in China, from 1911 through to 1949, had brought rapid modernisation, a start to elections and lively engagement with the rest of the world, which China was not to see again until recently. Many gifted people who had been working overseas returned to help build the new China. But Mao soon enough purged them, communalised farming, seized private property and sought to develop a class-consciousness derived from Karl Marx's European theory.

In 1958-1959 Mao launched his Great Leap Forward in a vain attempt to industrialise China to rival the Soviet Union. More than 30 million died, chiefly of starvation.

After the party's more pragmatic wing, led by Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping, seized the steering wheel (1960-1962), the ageing Mao engineered the decade-long Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) to shake them off. He succeeded, with a vengeance. Liu died in appalling circumstances. But Deng proved the great survivor. "All is chaos under heaven; the situation is excellent," Mao crowed. But immediately after the dark omen of the Tangshan earthquake near Beijing killed about 250,000 people, Mao died. Soon Deng assumed control (1978-1979) and announced China's great new kai fang (open door) era.

This was at first restricted to an economic opening, starting with a return to family farming. But it has since led to the gradual opening of personal space, too, for people to choose their own lifestyles as well as to do business, as long as they do not challenge the party. This evolution is typified by the word tongzhi — meaning same interest or inclination — whose use as the equivalent of the Russian tovarich, or comrade, was forcefully propagated by Mao. In recent times it has been appropriated by China's gay community.

China's communist era can thus be divided into halves. During the first half, under Mao, the country went backwards in many areas, literacy being a great exception, while health care also improved. In the second half, under Deng, China started to reclaim its role as a superpower, but one with a capacity and desire to project itself far beyond the empires of old. And it has retreated from a reliance on charismatic leadership, to a more routine and stable governance via committeemen.

Crucially for the party's survival, it has delivered on Deng's unwritten contract with the Chinese people, which was reinforced with fresh economic liberalisations after the 1989 protests: we guarantee your living standards keep improving, you let us rule as we've been accustomed.

Corruption, a yawning wealth gap, frustration at the failure to introduce the rule of law and a growing sense of entitlement rather than gratitude among younger Chinese sound warnings to which the party is striving to respond. Only the brave would bet against the party reaching its centenary and beyond. For all its adaptability, it is the same party, with a growing proportion of its top cadres comprising taizidang or princelings — their status guaranteed by heredity — including leader-in-waiting Xi Jinping.

The cadres (or professional revolutionaries) rule a people whose tastes, interests and experiences are changing much faster than theirs — but constant, intense polling alerts the party to changes that pose any threat, and the "net police" use their unlimited access to mobiles and internet use to profile much of the population. Recently, in Qingdao on International Consumer Rights Day, Han Nan hired nine workers to smash his Lamborghini Gallardo "to protest against bad service" by his car dealer because, he claimed, he had no other recourse. As a confused party cadre might ask, "What would Mao have done?" He might have celebrated that the people were driving Lamborghinis. Or turned in his grave, if he were buried. But he's not. He is on display, in the heart of the capital, as if to underline that for all China's changes, he and the party he forged remain at the centre of life 90 years on.

** End of article