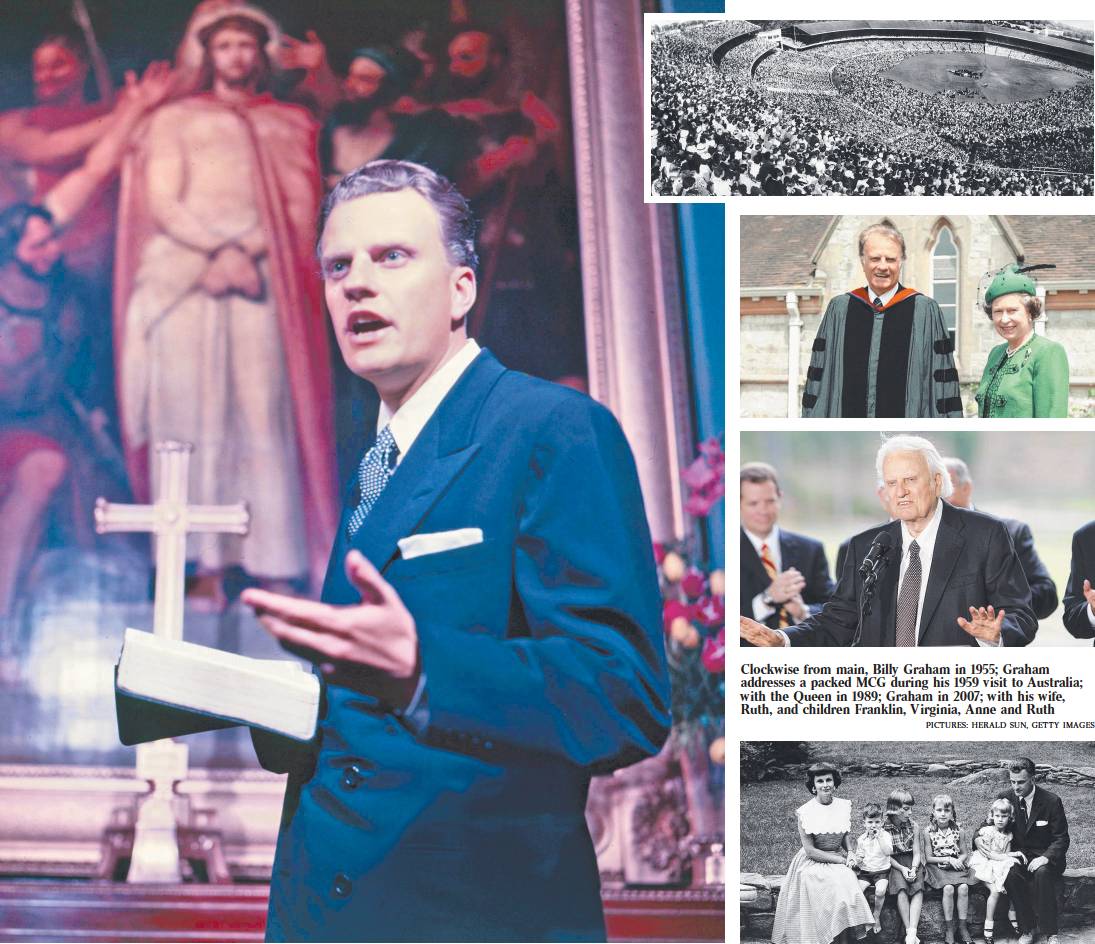

A great eulogy following some terrific photos

The Australian Feb 23, 2018

Billy Graham was the best known preacher of modern times

Billy Graham was relatively unknown in 1949 when William Randolph Hearst heard him preaching at a rally in Los Angeles. The magnate probably cared more about selling newspapers than "being saved", but he could tell charisma when he saw it. He dispatched a pithy note to his editors: "Puff Graham". Within days he was a national celebrity.

By that point Graham had set out his stall to evangelise the world. A year before, he had gathered his advisers in a hotel room in Modesto, California, and drawn up what became known as the "Modesto Manifesto", a range of measures designed to avoid controversy and criticism, such as ensuring that the money they raised was distributed fairly. Most notably they came up with what became known as the "Billy Graham rule", which stated that he would never be alone with any woman who was not his wife, Ruth.

"From that day on, I did not travel, meet or eat alone with a woman other than my wife," Graham wrote. "We determined that the Apostle Paul's mandate to the young pastor Timothy would be ours as well, 'Flee … youthful lusts.' " The rule held good for his entire life. He even had a private dinner with Hillary Clinton relocated to a hotel dining room.

Years later his grandson Will, who is also a preacher, spoke about the measures Graham's aides would take to avoid the whiff of scandal. "When my grandfather would check into a hotel, a man would go inside the room and look under the bed and into the closets. What they were afraid of was that someone had sneaked into the room, like a naked lady with a photographer, and she'd jump into his arms and (the photographer) would take a picture and they'd frame my granddaddy."

The Billy Graham rule allowed him to capitalise on his film star good looks — he turned down several offers from Hollywood — with no risk of a sullied reputation and he went on to become the best-known Christian evangelist of modern times. For more than 40 years he led his worldwide "crusades", as he termed his mass conversion campaigns, assisted, besides his features, by what Time magazine called "trumpet lungs".

Tall, handsome, blue-eyed and square-jawed, Graham had the personal magnetism common to the best proselytisers. He was the master of the dramatic gesture, thumping his Bible as he urged vast crowds to change their ways. "Are you frustrated, bewildered, dejected, breaking under the strains of life? Then listen for a moment to me. Say yes to the saviour tonight and in a moment you will know such comfort as you have never known." He would invite sinners to come forward and be saved. Thousands stepped up to face Graham's retinue of pastors.

"The Bible says …" was probably the most familiar phrase he used to coax and caress large numbers, and his approach proved to have broad appeal across the religious sectarian divide. It is estimated that he preached to 210 million people; all his 18 books were bestsellers. He regularly featured in Gallup's annual poll of the 10 most admired people in the world.

Graham's brand of popular fundamentalism, however, did not go down well with more cerebral Christians. He admitted that he was no intellectual and paid little attention to changing fashions of theology. Michael Ramsey, the former archbishop of Canterbury, was among those who thought a more thoughtful approach to religion was required. Others warned that Graham's message was dangerously simplistic.

Others described him as a "natural salesman" who cleverly adapted modern advertising techniques to "sell God". Indeed, as a young man Graham worked across the Carolinas as a door-todoor salesman for the Fuller Brush Company and made more money than anyone else. "Selling those brushes became a cause to me," he recalled. "I was dedicated to it and the money was secondary. I felt that everybody ought to have Fuller brushes as a matter of principle."

Graham experienced an evangelical conversion when he was 16 at a revival meeting addressed by preacher and temperance leader Mordecai Ham. "I didn't have any tears, I didn't have any emotion, I didn't hear any thunder, there was no lightning," he recalled. "But right there, I made my decision for Christ. It was as simple as that, and as conclusive."

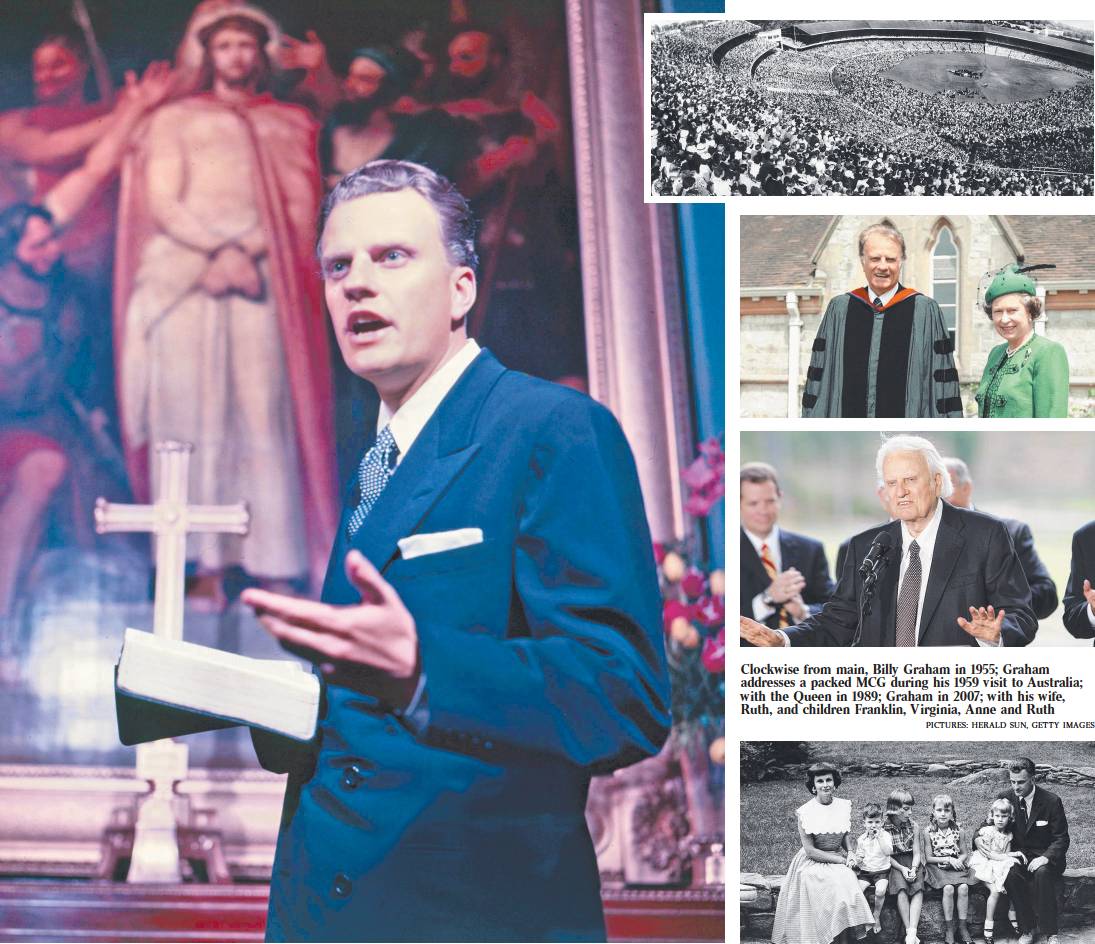

He first visited Britain after World War II and later counted the Queen as a friend and confidante. In 1954 the Evangelical Alliance invited him to conduct a series of revival meetings at the Harringay Arena in London, which could hold 12,000 people. It was booked for three months and was filled every night. The visit culminated in a packed final meeting at Wembley Stadium.

Increasingly surrounded by all the paraphernalia of sophisticated modern communications, Graham remained essentially an oldfashioned figure, a product of the certainties of the Bible Belt. To Time he was "the Pope of Protestant America".

William Franklin Graham was born on November 7, 1918, on a dairy farm near Charlotte in North Carolina. His father, also named William, and mother, Morrow, reared Billy and his three younger siblings as Presbyterians. When prohibition ended in 1933, William gave Billy a lifelong aversion to alcohol by making him drink beer until he was sick.

Graham's first ambition was to be a baseball player, but after his conversion he became a student at the Florida Bible Institute. Aged 19, he recalled, he became convinced that he had a vocation as an evangelist preacher while walking on a golf course. "I finally gave in while pacing at midnight on the 18th hole. 'All right, Lord,' I said. 'If you want me you've got me'."

He would practise preaching in a swamp where birds, alligators and bullfrogs were his congregation. He moved from his parents' Presbyterianism to the more conservative Southern Baptists and was ordained as one of their ministers in 1940.

In that year he became an undergraduate at Wheaton College, the leading conservative evangelical college, near Chicago, where he studied anthropology. He started his first full-time ministry in 1943 at Western Springs in suburban Chicago and presented a weekly radio program.

In the same year he married Ruth Bell, a fellow Wheaton student who had been born in China to missionary parents. She shared Graham's fervour and was all set to become a missionary until

Graham persuaded her that God wanted them to marry. Graham intended to become an army chaplain, but after applying for a commission he contracted mumps and instead joined the international evangelist organisation Youth for Christ and hit the road with his travelling crusades. His strong anti-communist message struck home as the Cold War intensified. "Either communism must die, or Christianity must die, because it is actually a battle between Christ and Antichrist," he said.

In 1957 Graham invited Martin Luther King to join one of his crusades. They became friends and in 1963 Graham put up bail when King was arrested in Birmingham, Alabama. As long ago as 1953 Graham had torn down barriers segregating blacks and whites at a meeting in Chattanooga, Tennessee, telling ushers to leave them down "or you can go on and have the revival without me". He once insisted to a member of the Ku Klux Klan that "there is no scriptural basis for segregation".

At the same time he became attached to Britain, even though he was shocked at finding couples "openly smooching" in London's parks during one visit in 1959. He preached more than once before the Queen at the Royal Chapel in Windsor Great Park, and on one occasion she rehearsed her Christmas speech in front of him and asked for his suggestions. He was also a regular guest at Downing Street, where he was received by prime ministers from Winston Churchill to Margaret Thatcher. He made his last visit in 1984, after which the Church of England was inundated with applications from people who wanted to become priests. He was awarded an honorary knighthood in 2001.

His friendship with the Queen grew — the Netflix series The Crown shows them meeting alone, although the "Billy Graham rule" would have militated against that eventuality. "I always found her very interested in the Bible and its message," he wrote. "After preaching at Windsor one Sunday, I was sitting next to the Queen at lunch. I told her I had been undecided until the last minute about my choice of sermon and had almost preached on the healing of the crippled man in John 5. Her eyes sparkled and she bubbled over with enthusiasm, as she could do on occasion. 'I wish you had!' she exclaimed. 'That is my favourite story.' "

In Graham's later years his tours became increasingly international. He preached to unprecedented multitudes in South Korea, reportedly to more than a million people on one occasion. He arrived in Australia on February 12, 1959, to begin his Southern Cross Crusade, his first to Australia. It lasted almost four months, and he visited Melbourne, Launceston, Hobart, Sydney, Brisbane, Canberra, Adelaide and Perth attended by more than three million Australians. He drew a record 143,000 people to the Melbourne Cricket Ground and 150,000 came to a double meeting at the Sydney Cricket Ground and adjoining showground.

He also made several visits to countries behind the Iron Curtain. In 1978 he was invited to preach at Wawel Cathedral in Cracow by the archbishop of Cracow, Karol Wojtyla, who became Pope John Paul II a few days later.

After his early days in Chicago, Graham never held a settled ministry but maintained contact with a wide constituency through more than two dozen books, countless broadcasts, starting with The Hour of Decision on NBC radio, and a weekly syndicated newspaper column read by five million people. He formed an Evangelistic Association that administered his affairs, paid him a relatively modest salary and organised his religious films, the TV coverage of his meetings and two monthly magazines, Decision and Christianity Today.

He organised a disaster relief program for the developing world and refused to conduct meetings in South Africa until he was assured the country would not be racially segregated.

He won the confidence of successive presidents who saw the huge potential of harnessing Graham's anti-communism and his belief that the Western economic model of free enterprise was blessed by God. His singular role in the White House, he prayed with every US president from Harry S. Truman to Barack Obama, earning him the nickname "America's Pastor". Graham estimated that his support was worth 16 million votes. At the inauguration of Richard Nixon as president he declared: "Thou has permitted Richard Nixon to lead us at this momentous hour of our history." The pair enjoyed a warm friendship, but Graham distanced himself from US politics after the Watergate scandal. When 400 hours of Nixon tapes were released in February 2002, Graham was further embarrassed. As well as anti-Semitic comments from Nixon, the tapes recorded contemptuous remarks about Jews by Graham, who was recorded as saying: "They're the ones putting out the pornographic stuff. This stranglehold has got to be broken or the country's going down the drain." From a man who had publicly advocated reconciliation between Christians and Jews, this was shocking, and Graham rapidly backtracked when the tapes came to light.

It was from the hands of Ronald Reagan that Graham, a lifelong registered Democrat, received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1983. He also was credited with shunting a young George W. Bush, a dissolute drunk, back on to the straight and narrow with a heartfelt talk. One of Graham's most memorable later public appearances — his closing years were clouded by Parkinson's disease, which was diagnosed in 1991 — was in the rotunda of the US Capitol in Washington, DC, where he was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 1996. Despite all this recognition, most non-evangelical Christians persisted in seeing him as a figure more reminiscent of a 19thcentury revivalist rather than representative of the broad sweep of 20th-century religion. A measure of originality could perhaps be claimed for Graham in his realisation, whether conscious or not, that in a world of mobile and urbanised populations, constantly bombarded by the mass media and other distractions, it was necessary to make a loud noise and have a strong organisation to receive any attention at all. The message had to be as simple as possible because of the scale of the gatherings and because of widespread ignorance of basic Christian faith. Many people undoubtedly were helped spiritually by Graham's crusades; others may have been put off.

What remains undeniable is that, within his frame of reference, Graham's life was a remarkably impressive example of dedicated, unremitting Christian service. Under the spotlight of relentless publicity, by no means all of it kind, he retained his good humour and a sense of proportion about himself. As Christian evangelism began to suffer from a slew of scandals involving sexual misconduct and financial embezzlement, Graham emerged unscathed.

His wife was an independent woman, ready to stand up to him. Most notably, she refused to join his Baptist church, remaining in the firm Presbyterian faith of her parents. Graham once quoted Ruth on modern morality: "If God doesn't punish America, he'll have to apologise to Sodom and Gomorrah." She died in 2007, aged 87. "Ruth was my life partner and we were called by God as a team," Graham said. "No one could have borne the load that she carried. She was a vital and integral part of our ministry." He cherished the times when he could retreat to his modest log cabin in the mountains with Ruth.

In his final years Graham largely remained in his mountaintop home in Montreat, North Carolina, occasionally receiving visits from politicians, including Obama in 2010.

His final book, Where I Am: Heaven, Eternity and Our Life Beyond the Now, appeared in 2015.

Graham is survived by his five children, all of whom followed the God-fearing path.

In his later years Graham, his sight and hearing fading, received around-the-clock care, always from two nurses, "for accountability purposes", said his grandson Will. The Billy Graham rule held fast until the end.

THE TIMES