JRR Tolkien

By JOHN GARTH

Daily Mail UK

PUBLISHED: 28 April 2019

In July 1916, JRR Tolkien emerged from a 50-hour hell of cordite and blood on the Somme battlefield.

It was two weeks after the start of the great offensive and his battalion had been attacking the fiercely held German hilltop stronghold of Ovillers-la-Boisselle.

Returning to the hut he was sharing at a nearby village, and desperate for rest, instead Tolkien found a letter from one of his closest friends. ‘I saw in the paper this morning that Rob has been killed,’ it said. ‘Do please stick to me, you and Christopher.’

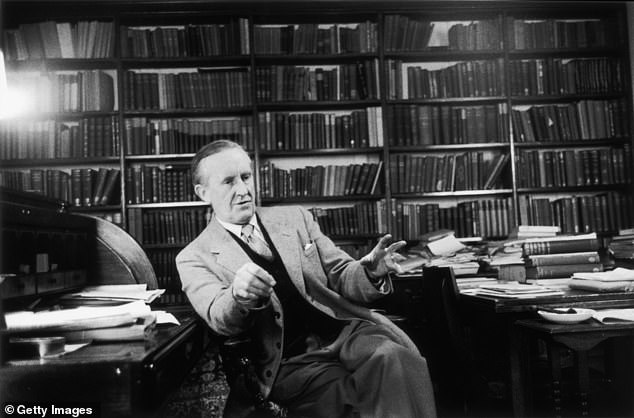

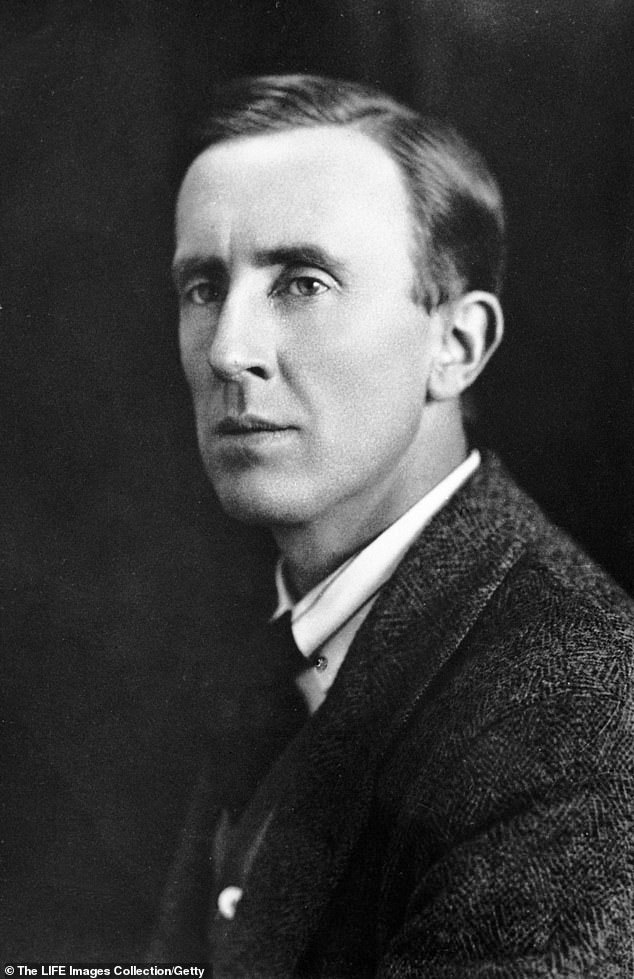

JRR Tolkien in the Forties

The writer was Geoffrey Bache Smith and the other survivor was Christopher Wiseman. The death of their friend Robert Quilter Gilson signalled the breaking of their schoolboy fellowship, one which had seen this quartet of brilliant young men determined to make their mark on the world as they went into the Great War.

But Tolkien had no time to come to terms with the shock. Almost immediately after the Ovillers attack, he was promoted to battalion signal officer, in charge of communications for about 700 men.

Later, Tolkien sat out at night in a Somme wood as dark and tangled as his thoughts, then wrote to Geoffrey Smith ‘Something has gone crack,’ he said. ‘I feel just the same to both of you – nearer if anything and very much in need of you. But I don’t feel a member of a little complete body now.’

Page 1 of Tolkien's letter Page 2

JRR Tolkien in the Forties

The writer was Geoffrey Bache Smith and the other survivor was Christopher Wiseman. The death of their friend Robert Quilter Gilson signalled the breaking of their schoolboy fellowship, one which had seen this quartet of brilliant young men determined to make their mark on the world as they went into the Great War.

But Tolkien had no time to come to terms with the shock. Almost immediately after the Ovillers attack, he was promoted to battalion signal officer, in charge of communications for about 700 men.

Later, Tolkien sat out at night in a Somme wood as dark and tangled as his thoughts, then wrote to Geoffrey Smith ‘Something has gone crack,’ he said. ‘I feel just the same to both of you – nearer if anything and very much in need of you. But I don’t feel a member of a little complete body now.’

Page 1 of Tolkien's letter Page 2

Tolkien’s wife, Edith Bratt

Though none of them could know it, Gilson’s death had actually put Tolkien on the road to changing the world singlehandedly.

Next week (May 2019) the story of the four friends finally gets a big-screen showing in a film titled simply Tolkien, with Nicholas Hoult, Derek Jacobi and Lily Collins.

Tolkien’s stories have never been more popular, with Peter Jackson’s two movie trilogies, The Lord Of The Rings and The Hobbit, grossing almost £4.5 billion at the box office.

Though the Somme was one of the greatest challenges he would face, John Ronald Reuel Tolkien had already had enough separations, bereavements and dashed dreams to last a lifetime.

Click here for a full timeline.

At three he was moved from southern Africa back to his parents’ English homeland. At four he lost his father, still in Africa, to typhoid fever. After a few happy years in Sarehole, Worcestershire – a village he remembered as ‘a kind of lost paradise’ – the family moved to Birmingham so he could attend the city’s best school, King Edward’s from 1903 - 1911.

When he was 12, the mother he revered slipped into a diabetic coma and died. He took refuge in language, learning Chaucer’s Middle English, the Old English of Beowulf, the Old Norse of the Viking sagas. He even invented languages of his own. All this and the still unforeseen war would eventually go into the brew of Middle-earth.

But there was another force behind Tolkien and his books – a force that opened the door so he could communicate his passions with a wider audience. He had to be brought out of himself, and what did it was love.

He and his brother Hilary were now wards of Francis Morgan, a kindly Catholic priest. Moving to new lodgings in 1908, Ronald laid eyes on the woman he would marry.

At 19, Edith Bratt was three years his senior, pretty, dark-haired and grey-eyed. She was also an orphan, and lonely and frustrated.

The youngsters would talk into the night, Tolkien at his window, Edith at hers. There were bike rides and ‘three great kisses’. At a favourite tea shop, they tossed sugar lumps into the hats of passers-by.

But Father Francis stopped it all dead. Foreseeing a brilliant future for Tolkien, he feared Edith would wreck his chances of Oxford. And she was Church of England. Tolkien was told to end the relationship.

In 1910 the boys were moved to new lodgings. Edith left Birmingham for Cheltenham.

But she had given Tolkien social confidence – and the drive to make a name for himself on the school rugby pitch. Here he nearly bit his tongue out. But he also discovered true friendship. It began with the attraction of opposites – the small, language-obsessed and Catholic Tolkien and the barrel-chested Methodist Christopher Wiseman.

Tolkien’s wife, Edith Bratt

Though none of them could know it, Gilson’s death had actually put Tolkien on the road to changing the world singlehandedly.

Next week (May 2019) the story of the four friends finally gets a big-screen showing in a film titled simply Tolkien, with Nicholas Hoult, Derek Jacobi and Lily Collins.

Tolkien’s stories have never been more popular, with Peter Jackson’s two movie trilogies, The Lord Of The Rings and The Hobbit, grossing almost £4.5 billion at the box office.

Though the Somme was one of the greatest challenges he would face, John Ronald Reuel Tolkien had already had enough separations, bereavements and dashed dreams to last a lifetime.

Click here for a full timeline.

At three he was moved from southern Africa back to his parents’ English homeland. At four he lost his father, still in Africa, to typhoid fever. After a few happy years in Sarehole, Worcestershire – a village he remembered as ‘a kind of lost paradise’ – the family moved to Birmingham so he could attend the city’s best school, King Edward’s from 1903 - 1911.

When he was 12, the mother he revered slipped into a diabetic coma and died. He took refuge in language, learning Chaucer’s Middle English, the Old English of Beowulf, the Old Norse of the Viking sagas. He even invented languages of his own. All this and the still unforeseen war would eventually go into the brew of Middle-earth.

But there was another force behind Tolkien and his books – a force that opened the door so he could communicate his passions with a wider audience. He had to be brought out of himself, and what did it was love.

He and his brother Hilary were now wards of Francis Morgan, a kindly Catholic priest. Moving to new lodgings in 1908, Ronald laid eyes on the woman he would marry.

At 19, Edith Bratt was three years his senior, pretty, dark-haired and grey-eyed. She was also an orphan, and lonely and frustrated.

The youngsters would talk into the night, Tolkien at his window, Edith at hers. There were bike rides and ‘three great kisses’. At a favourite tea shop, they tossed sugar lumps into the hats of passers-by.

But Father Francis stopped it all dead. Foreseeing a brilliant future for Tolkien, he feared Edith would wreck his chances of Oxford. And she was Church of England. Tolkien was told to end the relationship.

In 1910 the boys were moved to new lodgings. Edith left Birmingham for Cheltenham.

But she had given Tolkien social confidence – and the drive to make a name for himself on the school rugby pitch. Here he nearly bit his tongue out. But he also discovered true friendship. It began with the attraction of opposites – the small, language-obsessed and Catholic Tolkien and the barrel-chested Methodist Christopher Wiseman.

| Tolkien was oppressed by his war memories, like anyone else, but he had a gift for turning stress, anxiety and even nightmare into creativity |

|

They larked about and they argued, passionately but civilly. Others gravitated to them. Robert Gilson, son of the headmaster, was the social glue – a boy with no enemies. The group’s little kingdom was its office as pupil-librarians. Here they secretly brewed tea. Outside school, they met for more tea at Barrow’s department store. Members numbered about ten. They were the Tea Club and Barrovian Society – TCBS for short. These boys were the brightest and best at a school where you acted Aristophanes in the original Greek. At the annual Latin debate, Tolkien went one better – speaking Gothic, a long-dead cousin of English and Norse. Competitive, eccentric and often elusive, he was adored by his friends. For all his nerdiness, he was also an entertainer, a splendid mimic with a comedic knack.

Tolkien got to Oxford in October 1911, where his closest friend was a recent TCBS addition, Geoffrey Smith – forthright, passionate for Welsh and myth, and a practising poet. Tolkien, who had written nothing but parody, was impressed.

Just after war broke out in 1914, he realised his ambitions as a writer after a ‘Council’ in London at Wiseman’s house with Smith and Gilson.

In a string of poems, and in a little lexicon of ‘Elvish’, Tolkien began to craft Middle-earth, and the TCBS became its first fans.

They helped it take shape with their criticisms and suggestions, and they began to edge into the project. Wiseman set Tolkien’s poems to music, Smith wrote verse with overlapping ideas, and Gilson planned a book of designs.

You can think of the four as Tolkien’s first fellowship. Like the Fellowship in his epic The Lord Of The Rings, the TCBS had been plunged unexpectedly into war, found tremendous support in each other, and was then scattered to face different perils.

In 1915, Tolkien got his Oxford first in English and followed Smith into the Lancashire Fusiliers. Wiseman joined the Navy and – apart from the Battle of Jutland – spent most of the war safely in the Orkneys teaching ‘snotties’, naval recruits.

What Tolkien said next took the TCBS by surprise. He was about to be married.

Back in 1913, at the stroke of midnight as he turned 21, Tolkien had written to Edith Bratt renewing his vows of love. Her reply was a gobsmacker – she was engaged. But Tolkien took the train to Cheltenham and, in a single afternoon’s talk, won her back. He told the TCBS about the engagement but they were not at the wedding in March 1916. Hearing about it just a week beforehand, Gilson complained privately that it was ‘a complete surprise… as all his movements nearly always are’.

Edith took lodgings near her husband’s training camp. But almost immediately Tolkien’s orders arrived – he was bound for the Western Front. Parting from Edith ‘was like a death’, he said.

Smith and Gilson were in the disastrously over-confident massed assault on the first day of the Somme, 1 July 1916. It was Gilson who first became a statistic of war, killed the same day as he led his company across no-man’s-land.

If Tolkien learned one thing from war, it was the resilience and spirit of the ordinary privates, including the batmen who sorted out his kit and ran errands.

He later said they were the inspiration for Sam Gamgee, whose dogged loyalty and unexpected courage really bring the Lord Of The Rings quest to fulfilment.

Like the officer-figure Frodo Baggins in that epic, Tolkien was put out of action by a bite from a verminous, hateful arthropod. But this was no giant spider – it was a louse. On October 25 he visited the medical officer, complaining of a fever. He had contacted trench fever, which was caused by bites from the lice. He was sent home. Since the fever allowed him to escape from the front, it almost certainly saved his life.

After weeks in hospital, he returned to Edith at Great Haywood and convalesced.

But just before Christmas the second and worst blow fell. Wiseman wrote saying Smith had died of a shell wound. He had been wounded by a shell on November 29 while organising a football match for his men, miles from the front line, and died of his wounds on December 3.

Interestingly, some of Smith’s last words in a letter to Tolkien were: “May God bless you, my dear John Ronald, and may you say the things I have tried to say long after I am not there to say them, if such be my lot.”

The new biopic, which has not been endorsed by Tolkien’s family, puts Edith and the TCBS at the heart of Tolkien’s formative years. It also makes an emphatic connection between his war experiences and his famous writings. The film often breaks with fact and chronology, and misleadingly implies that the carnage stifled his writings. That is what happened to others – there was a decade’s near silence before the famous trench memoirs began to flood out.

By contrast, Tolkien’s first epic, The Fall Of Gondolin, came spilling out of him in convalescence and hospital straight after the Somme. The elf-city of Gondolin is destroyed by machines that are part-dragon, part-tank.

A dance in the woods by Edith in 1917 inspired the core story of the lovers Beren and Lúthien – so important to Tolkien that those two names are now carved, at his request, on the gravestone they share in Oxford.

Tolkien was oppressed by his war memories, like anyone else, but he had a gift for turning stress, anxiety and even nightmare into creativity.

What delayed his progress towards publication was his career as an academic at Oxford, his commitment to family life with Edith and four children, and his sheer perfectionism. What brought the TCBS dream to fruition, first, was Tolkien writing The Hobbit for his children and its publication in 1937. Second, there was his friendship with CS Lewis, an Oxford don as poetic as Smith, sociable as Gilson and argumentative as Wiseman. Lewis pushed Tolkien not only to finish The Lord Of The Rings over 12 long years, but to make it his masterpiece.

Published in 1954–5, it was understandably mistaken for a Second World War book. But the formative war had been the First. Tolkien protested, adding: ‘By 1918 all but one of my close friends were dead.’ It sounds counter-intuitive to say this epic fairy story is about modern war, but it is.

Tolkien’s great contribution is his expertise on the medieval values of courage and heroism that other trench writers saw as casualties of their war. But hobbits – with their down-to-earth nature, their pocket handkerchiefs and their post offices – are like people from his own generation, thrust into a world of danger.

So Tolkien brilliantly intertwines two stories. There is a medieval war, with wild horns heralding one of the most stirring cavalry charges ever committed to paper. And there is a long, psychological slog by officer Frodo and batman Sam through a vast and pitiless no-man’s-land. Together, they make a timeless myth.

In the school of hard knocks, Tolkien had learned a thing or two about survival and recovery.

** End of Page

Go Top

JRR Tolkien in the Forties

The writer was Geoffrey Bache Smith and the other survivor was Christopher Wiseman. The death of their friend Robert Quilter Gilson signalled the breaking of their schoolboy fellowship, one which had seen this quartet of brilliant young men determined to make their mark on the world as they went into the Great War.

But Tolkien had no time to come to terms with the shock. Almost immediately after the Ovillers attack, he was promoted to battalion signal officer, in charge of communications for about 700 men.

Later, Tolkien sat out at night in a Somme wood as dark and tangled as his thoughts, then wrote to Geoffrey Smith ‘Something has gone crack,’ he said. ‘I feel just the same to both of you – nearer if anything and very much in need of you. But I don’t feel a member of a little complete body now.’

Page 1 of Tolkien's letter Page 2

JRR Tolkien in the Forties

The writer was Geoffrey Bache Smith and the other survivor was Christopher Wiseman. The death of their friend Robert Quilter Gilson signalled the breaking of their schoolboy fellowship, one which had seen this quartet of brilliant young men determined to make their mark on the world as they went into the Great War.

But Tolkien had no time to come to terms with the shock. Almost immediately after the Ovillers attack, he was promoted to battalion signal officer, in charge of communications for about 700 men.

Later, Tolkien sat out at night in a Somme wood as dark and tangled as his thoughts, then wrote to Geoffrey Smith ‘Something has gone crack,’ he said. ‘I feel just the same to both of you – nearer if anything and very much in need of you. But I don’t feel a member of a little complete body now.’

Page 1 of Tolkien's letter Page 2

Tolkien’s wife, Edith Bratt

Though none of them could know it, Gilson’s death had actually put Tolkien on the road to changing the world singlehandedly.

Next week (May 2019) the story of the four friends finally gets a big-screen showing in a film titled simply Tolkien, with Nicholas Hoult, Derek Jacobi and Lily Collins.

Tolkien’s stories have never been more popular, with Peter Jackson’s two movie trilogies, The Lord Of The Rings and The Hobbit, grossing almost £4.5 billion at the box office.

Though the Somme was one of the greatest challenges he would face, John Ronald Reuel Tolkien had already had enough separations, bereavements and dashed dreams to last a lifetime.

Click here for a full timeline.

At three he was moved from southern Africa back to his parents’ English homeland. At four he lost his father, still in Africa, to typhoid fever. After a few happy years in Sarehole, Worcestershire – a village he remembered as ‘a kind of lost paradise’ – the family moved to Birmingham so he could attend the city’s best school, King Edward’s from 1903 - 1911.

When he was 12, the mother he revered slipped into a diabetic coma and died. He took refuge in language, learning Chaucer’s Middle English, the Old English of Beowulf, the Old Norse of the Viking sagas. He even invented languages of his own. All this and the still unforeseen war would eventually go into the brew of Middle-earth.

But there was another force behind Tolkien and his books – a force that opened the door so he could communicate his passions with a wider audience. He had to be brought out of himself, and what did it was love.

He and his brother Hilary were now wards of Francis Morgan, a kindly Catholic priest. Moving to new lodgings in 1908, Ronald laid eyes on the woman he would marry.

At 19, Edith Bratt was three years his senior, pretty, dark-haired and grey-eyed. She was also an orphan, and lonely and frustrated.

The youngsters would talk into the night, Tolkien at his window, Edith at hers. There were bike rides and ‘three great kisses’. At a favourite tea shop, they tossed sugar lumps into the hats of passers-by.

But Father Francis stopped it all dead. Foreseeing a brilliant future for Tolkien, he feared Edith would wreck his chances of Oxford. And she was Church of England. Tolkien was told to end the relationship.

In 1910 the boys were moved to new lodgings. Edith left Birmingham for Cheltenham.

But she had given Tolkien social confidence – and the drive to make a name for himself on the school rugby pitch. Here he nearly bit his tongue out. But he also discovered true friendship. It began with the attraction of opposites – the small, language-obsessed and Catholic Tolkien and the barrel-chested Methodist Christopher Wiseman.

Tolkien’s wife, Edith Bratt

Though none of them could know it, Gilson’s death had actually put Tolkien on the road to changing the world singlehandedly.

Next week (May 2019) the story of the four friends finally gets a big-screen showing in a film titled simply Tolkien, with Nicholas Hoult, Derek Jacobi and Lily Collins.

Tolkien’s stories have never been more popular, with Peter Jackson’s two movie trilogies, The Lord Of The Rings and The Hobbit, grossing almost £4.5 billion at the box office.

Though the Somme was one of the greatest challenges he would face, John Ronald Reuel Tolkien had already had enough separations, bereavements and dashed dreams to last a lifetime.

Click here for a full timeline.

At three he was moved from southern Africa back to his parents’ English homeland. At four he lost his father, still in Africa, to typhoid fever. After a few happy years in Sarehole, Worcestershire – a village he remembered as ‘a kind of lost paradise’ – the family moved to Birmingham so he could attend the city’s best school, King Edward’s from 1903 - 1911.

When he was 12, the mother he revered slipped into a diabetic coma and died. He took refuge in language, learning Chaucer’s Middle English, the Old English of Beowulf, the Old Norse of the Viking sagas. He even invented languages of his own. All this and the still unforeseen war would eventually go into the brew of Middle-earth.

But there was another force behind Tolkien and his books – a force that opened the door so he could communicate his passions with a wider audience. He had to be brought out of himself, and what did it was love.

He and his brother Hilary were now wards of Francis Morgan, a kindly Catholic priest. Moving to new lodgings in 1908, Ronald laid eyes on the woman he would marry.

At 19, Edith Bratt was three years his senior, pretty, dark-haired and grey-eyed. She was also an orphan, and lonely and frustrated.

The youngsters would talk into the night, Tolkien at his window, Edith at hers. There were bike rides and ‘three great kisses’. At a favourite tea shop, they tossed sugar lumps into the hats of passers-by.

But Father Francis stopped it all dead. Foreseeing a brilliant future for Tolkien, he feared Edith would wreck his chances of Oxford. And she was Church of England. Tolkien was told to end the relationship.

In 1910 the boys were moved to new lodgings. Edith left Birmingham for Cheltenham.

But she had given Tolkien social confidence – and the drive to make a name for himself on the school rugby pitch. Here he nearly bit his tongue out. But he also discovered true friendship. It began with the attraction of opposites – the small, language-obsessed and Catholic Tolkien and the barrel-chested Methodist Christopher Wiseman.